Milk, methane and motherly love

Cows that have just calved are more susceptible to diseases. A doctoral student from ETH Zurich has been studying why their immune system does not work properly during this phase. Globe visited her at work.

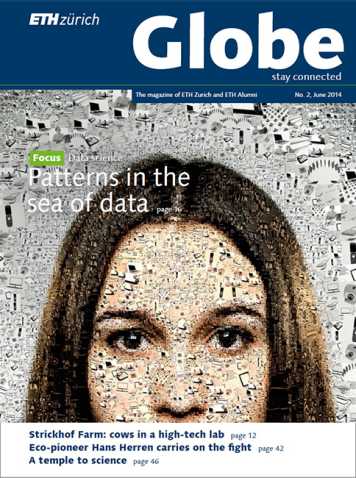

This article has been published in Globe, no.

2/June 2014:

Read the magazine online or subscribe to the print magazine.

If there had been a cockerel at Strickhof Farm in Lindau-Eschikon, our feathered friend would have been crowing by now. For it is still early on this wet morning. However, the day on the farm doesn’t just start at an unearthly hour for the farmhands. The biologist Susanne Meese is also already up and about. She is a doctoral student in the Animal Nutrition Group of Professor Michael Kreuzer and is today conducting tests on three pregnant cows. One by one, the animals are led into a special chamber where their energy consumption is measured. “I want to find out how the energy balance differs before as well as after calving and how it influences the immune system”, explains Meese.

Impressions

-

Susanne Meese leading her test animal Rahel back to the stable. This doctoral student from ETH Zurich has just conducted a successful test measurement with the pregnant cow in the respiration chamber. -

Strickhof employee Sabine Rinderknecht preparing to take the test animal Ibiza into the test chamber. -

Doctoral student Susanne Meese (in the foreground) from ETH Zurich, and Sabine Rinderknecht, a member of staff at Strickhof Farm. Together they lead Rahel, the pregnant cow, into the respiration chamber.

At the moment, the test animals are still in the cowshed with the other cows, while Meese prepares the two respi?ration chambers. She heaves open the heavy double doors, thanks to which the chambers can be sealed later on. Once the chamber is airtight, fresh air can only flow in via a pipe in a controlled manner and the used air is conducted away to various analysis instruments in the adjacent room.

Meese stocks the chambers with water and hay, scatters straw in the grate and slides in the drawers underneath to collect the dung. Because the chambers are raised slightly, Meese has to lug in some wooden pallets and build a small step. “The chambers are ready. We can call Sabine and fetch Jutta”, she announces. Sabine Rinderknecht, the head of milk production and livestock fattening at Strickhof, is helping to transport the cows between the stable and the chamber today. Jutta is the first test animal.

By now, it is bucketing down outside. With her hood pulled down over her face and her overalls tucked into her wellies, Meese hurries across the yard to the cowshed. There it is warm, dry and smells of fresh straw – and, as you might expect, of dung. Folk music is blasting out of the radio. Around thirty cows are lined up in two rows on either side. One of them is Jutta, a Holstein cow. Sabine Rinderk?necht makes her stand up. Her two neighbouring animals also have to get up, for otherwise the risk of Jutta injuring them with a stray hoof is too great.

Getting used to the chamber

Jutta is actually supposed to clamber onto the scales behind the cowshed now, but Meese postpones the weighing until later in the hope that the rain will have eased off by the time the cow has completed her three-hour stint in the chamber. Jutta seems perfectly happy as she trots calmly across the yard. Suddenly, however, she stops dead outside the entrance to the next building. “She doesn’t know this place yet”, whispers Meese. “That’s why she’s a bit wary.”

Overcoming this confusion is the name of the game for today. After all, stress could influence the readings. That’s why Jutta and the other two test animals, Rahel and Ibiza, will only spend three hours in the chamber at first – to get used to it. The measurements are only taken for test pur?poses, too. The three pregnant cows won’t take part in the actual experiment for another couple of weeks, when they will spend two whole days in the chamber for the first time.

Thanks to some soft words and a gentle push, however, the two companions manage to get Jutta into the chamber without any trouble – but not without her first depositing a great, big cowpat barely three metres from the door. Later on, Ibiza, the third test animal, steps straight in it. Before the door has even closed, Jutta is already munching away. “That’s a good sign”, beams Meese. The hay in the respira?tion chamber is particularly tasty, like a Sunday dinner. They don’t get that in the cowshed. “The good food in the chamber is supposed to woo the animals into a positive frame of mind”, she says.

Meese has to weigh the food before tipping it into the trough – this is the only way of knowing how much energy the cows take on board. The oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide as well as methane emissions in the respi?ration chamber are also measured. Using both the data gained and default vales, the scientist can calculate how much energy the animal consumes. Meese conducts the two-day experiment four times with every cow – five weeks and a fortnight before calving as well as two and twelve weeks afterwards. She then compares the different meas?uring days.

Meese leaves the door open so that Rahel, the next test animal, can see her companion in the chamber. This reas?sures her. After all, cattle are not loners, which is why a mirror in the chamber tricks them into thinking that they have got company. Rahel is much feistier than Jutta. Sabine Rinderknecht needs to summon up a lot of strength to lead her. And Susanne Meese is not afraid to get her hands dirty, either. Having grown up on a stud farm, she is no stranger to handling big quadruped. The cow has also got a boil on its foot. Although it is harmless and already starting to heal, Meese notes it down for good measure as the infection could influence her data. After all, the doctoral student is especially interested in the animals’ immune systems.

Sacrifice for offspring

It is not uncommon for new mother animals to suffer from infections or other health problems after calving. What’s more, the amount of energy they consume during this phase is enormous. After the roughly nine-month gesta?tion period, the exertions of giving birth and producing milk sap their energy reserves. So the young researcher is studying how the negative energy balance weakens the im?mune system. In order to test her hypothesis, Meese takes blood samples from the cows and uses them to produce cell cultures in the lab of Susanne Ulbrich, a new professor. Meese then adds a so-called mitogen, a substance that mimics an infection. Immune cells from the blood of cows that have just calved respond less strongly to the mitogen than immune cells from the blood of pregnant cows. Meese is studying why, based on various series of tests. “For the calf to survive, the mothers invest in milk production”, she ex?plains. Furthermore, high-yield dairy cows produce up to six times more milk than the calf needs to survive. “This investment in milk production can come at the expense of the immune response”, Meese sums up.

But the doctoral student does not only work on the farm in overalls and rubber wellies. She also dons a lab coat and wields a pipette at a sterile bench. “I like the variety that my doctoral project offers”, says the biologist, who is super?vised by Angela Schwarm.

Meese closes the double doors to the chambers and van?ishes into the computer room next door, where she can observe Jutta and Rahel on webcams. She switches on the measuring apparatus to analyse the used air from the chambers. The oxygen, carbon dioxide and methane curves appear on the screen. On the monitor, Meese notices that Jutta’s trough is getting low on food, so she fetches some more hay. She has to enter the chamber through a side door now, as the large doors are no longer allowed to be opened; that would distort the reading.

Body mass index for cows

It is still pouring down outside. The three hours are up. Now Meese is unable to avoid the detour across the scales before Jutta is allowed to return to the stable. The scales consist of a plate embedded in the ground that is easily big enough to weigh a lorry if you really wanted to. Meese measures the weight mechanically. It takes time for all the levers to be adjusted properly. And Jutta refuses to stay still. She keeps trying to wriggle free. No wonder. How many ladies voluntarily climb on a set of scales? Especially when it dis?plays an unflattering 790 kilograms.

Besides weight, the so-called body condition score is also a key measure of a cow’s health – a kind of body mass index for cattle. Susanne Meese assesses different parts of the body, such as how strongly certain bones stick out. Depending on the result, she awards points and thus determines the score. And Jutta’s is distinctly average. Even though a good three quarters of a ton is heavy for a pregnant cow, Jutta is patently a large specimen with a broad physique. “For me, the changes in the course of the pregnancy or in the weeks after the birth are more interesting than the absolute figures.” After all, the degree of weight loss could also have an impact on the immune system.

As yet, Meese is still unable to draw any definitive con?clusions about her research results. She needs to gather more data first. Next week it is Isabelle’s turn for her final session before giving birth, followed by Fina, whose calf has already been born. For today, Ibiza still needs to do her practice run in the chamber before she also embarks on her four-part series of tests in three weeks’ time.

Everything went like clockwork today. After their success?ful acclimatisation in the respiration chamber, Jutta, Rahel and Ibiza are back safe and sound among their kind in the stable. Now all that remains for Meese to do is clean up. A lot of dung has accumulated in the course of the day – and not just in the trays especially provided underneath the grate. But that’s all part and parcel of doing a doctorate at ETH Zurich, too.

Agrovet-Strickhof

ETH Zurich, the University of Zurich and the Canton of Zurich’s Office of Landscape, Agriculture and Environment are planning a joint educational and research centre at the present Strickhof site in Lindau-Eschikon. Thanks to this collaboration, the three institutions, all of which currently run their own facilities, are able to share livestock and infrastructure and thus benefit from specialist synergies. The costs of new and replace?ment buildings are to be shared equally between the canton and ETH Zurich. The construction work is scheduled for 2015.