New scanner could provide earlier diagnosis of dementia

The two ETH particle physicists Jannis Fischer and Max Ahnen are building a brain scanner that is ten times less expensive and much smaller than current models. Their ground-breaking work has earned them a place on the 2018 "30 Under 30" list published by the American business magazine Forbes.

They are barely thirty years old and are already actively involved in improving the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Max Ahnen (29) and Jannis Fischer (30) are developing a PET brain scanner that is not only less expensive, but also much more compact than those currently installed in hospitals. In recognition of their work, the US business magazine Forbes has included them on its “external page 30 Under 30 Europe” list 2018, in the category of Science & Healthcare. Forbes compiles this list every year to recognise “the most intelligent young entrepreneurs and inventors” in different disciplines. “We’re very proud to have made it onto the list,” says Jannis Fischer, who then jokes: “Next year we would have been too old to qualify!”

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) is an imaging method in nuclear medicine. It is mainly used to detect cancer, but also for neurological and cardiovascular diseases. It requires the intravenous injection of a mildly radioactive substance into the patient’s arm. An image is then generated of how this substance accumulates in different parts of the body, where it indicates the body part’s function.

PET scanners can help to diagnose certain neurological health conditions 10-20 years before doctors are able to do so by assessing the patient’s physical symptoms. The problem is that today, this is not done because these devices are very large and expensive. A conventional scanner takes up around 15 square metres of floor space and costs between 1.5 and 5.5 million Swiss francs.

Cheaper, smaller and more mobile

At ETH Zurich’s Institute for Particle Physics and Astrophysics, Ahnen and Fischer are working to improve this situation. The project was initiated by researchers and doctors from the University of Zurich and the University Hospital of Zurich. The provisional name for their invention is Brain PET (BPET) and it will be used to identify neurological disorders. These include brain tumours and diseases of the nervous system, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease, all of which cause dementia.

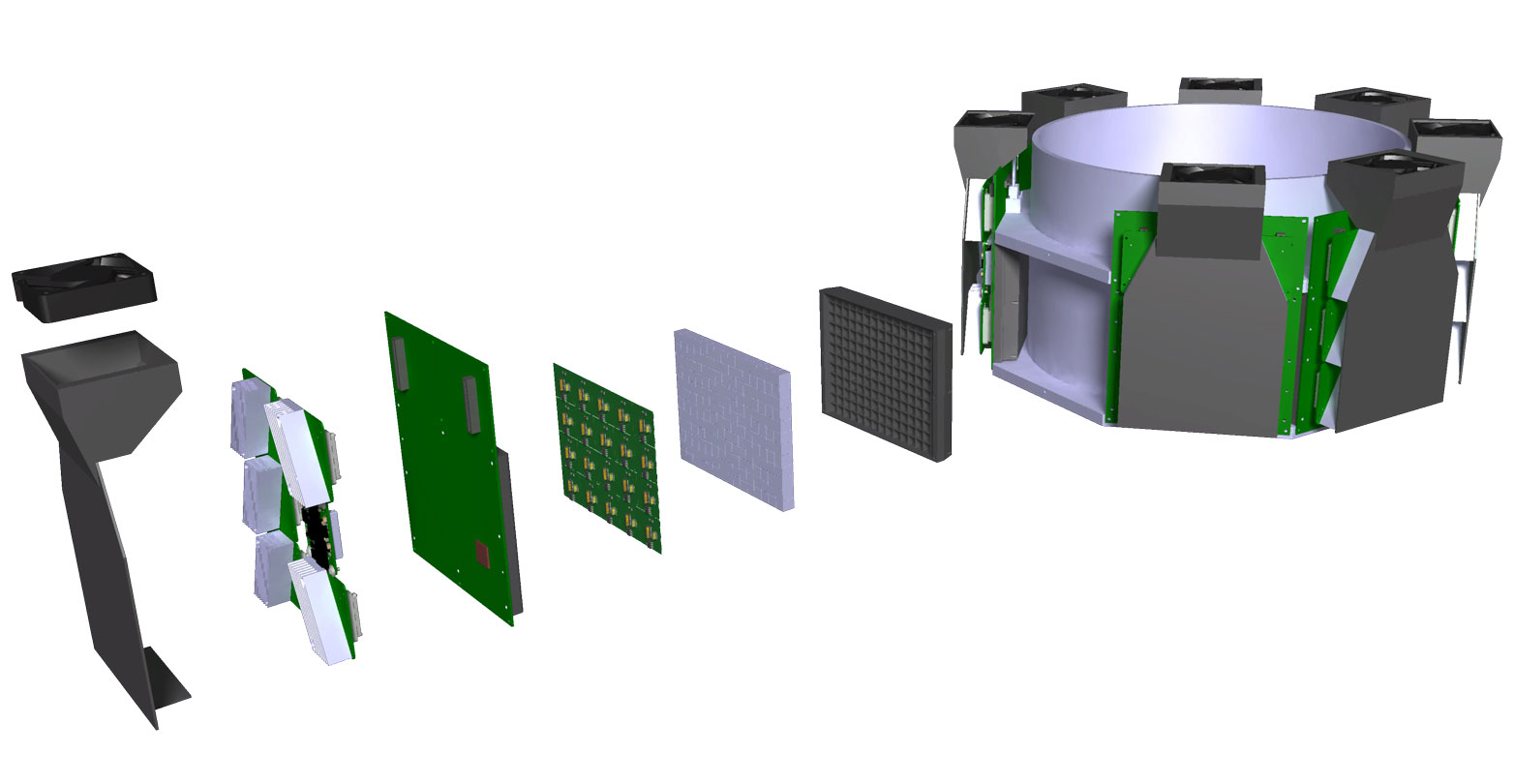

BPET is supposed to cost just a tenth of current PET machines and its footprint will be less than two square metres. “It looks a bit like a hair salon chair with an integrated hairdryer hood,” Ahnen says. Because of its size, it is much more mobile than conventional machines, and is therefore suitable for use not only in big hospitals, but also in smaller clinics in South America, Asia, or Africa.

Not only does the Brain PET technology cost less, but it is cheaper to use. The higher the frequency of use, the lower the cost of the radioactive tracer substances. PET scanners are currently the most expensive type of imaging equipment used in modern clinics, and many hospitals are unable to afford them. Fischer says: “We will be able to reach much wider sections of the population than in the past.”

That would not only benefit patients, but also their relatives. Both physicists had family members suffering from dementia. Ahnen comments: “It’s hard to watch someone’s personality gradually disintegrate.” As father of three small children, he is keen to improve the situation for the next generation.

New company about to be set up

BPET only exists on paper so far. The two scientists are currently in the process of setting up their new company, Positrigo, while also finishishing the construction of the prototype by September 2018. The financing is already in place: in June 2017 they won a Pioneer Fellowship. ETH Zurich and the ETH Foundation award this grant to scientists looking to develop highly innovative products, as long as they benefit society or have a commercial use. These grants are not awarded for basic research, however, but must be based on the applicants’ existing research activity.

Ahnen and Fischer already worked on PET scanners during and after their doctoral studies at ETH. Ahnen comments: “It was obvious to me that there was certainly room for improvement here.” Since the award of the Pioneer Fellowship, the project has really moved forward, Fischer says. The two physicists from Germany reckon ETH is the perfect environment for their work: “The close collaboration between medical doctors and particle physicists creates space for exciting new developments,” he says, and then adds: “The university is a hotbed of knowledge and a unique ecosystem of experts.”

The scientists hope to bring Brain PET onto the market in 2021. They claim this goal is “optimistic, but also realistic”. The timing is important: this date is also when many pharmaceutical companies plan to launch new Alzheimer’s drugs. The idea behind these drugs – fitting to early PET diagnosis – is that they can be used to combat dementia causing diseases before there is any physical deterioration of the cerebral matter.